🦞 Red Lobster

Delegation is coming: are we ready for it?

Welcome to this week's edition!

Unless you have been living under an AI-generated rock, you’ve probably seen your social media feeds filled with a red lobster emoji: the story of Clawdbot, now OpenClaw, and its accompanying AI agent social network.

Unlike the videos you may have seen, my goal is not to show you how it works technically. It’s to understand why it caught on like wildfire and what that reveals about the future of work.

Let’s dive in.

What the hell is OpenClaw?

Unlike chatbots that wait for prompts and respond with text, OpenClaw takes action on your behalf on your own computer. It can control parts of your system, use your apps and files, trigger workflows, and execute multi-step tasks.

Technically, OpenClaw isn’t a new AI model: it uses existing large language models as its brain. What makes it different is that it gives those models hands: system access, tool use, and the ability to operate software. You can get Claude and ChatGPT to do many of these things through MCP connections, but it requires several setup steps: OpenClaw just made it simpler.

Over the last week, people have experimented with three broad categories of use:

Personal automation and coordination - Many use it as an always-on executive assistant: checking inboxes, preparing daily briefs, organizing reminders, and flagging what needs attention. The appeal is offloading the small coordination work that fills the day - or like someone else did, automate sending messages to your partner (🙃).

Work and ops monitoring - Others have delegated operational tasks: monitoring release workflows, watching GitHub or issue trackers, updating to-do tasks, or alerting when jobs finish.

Custom workflows and experimentation. The rest have built custom skills, connected APIs, automated home setups, or created personal routines. Some plugged it into their notes or knowledge bases, asking it to recall information, summarize data, or connect ideas.

Obviously, this tool is a security nightmare. You’re essentially giving it keys to all your information, which it can store and potentially share or breach. But that’s not really the point: over 2 million people visited in one week, and many will gladly take the risk until something happens or until someone releases a more secure version.

What caught my attention is how it spread. For a long time, marketing has been about persuasion: telling a compelling story, building awareness, and convincing people something is valuable before they touch it. In AI, that model is shifting as the center of gravity moves from persuasion to participation.

The question is no longer “Did people understand it?” but “Did people try it?”.

So overall, I think one of the reasons OpenClaw spread more because it was easy to try, easy to show, and socially rewarding to talk about. Using it became a small signal of being early, curious, and AI-literate. It functioned as experiential marketing disguised as a tool.

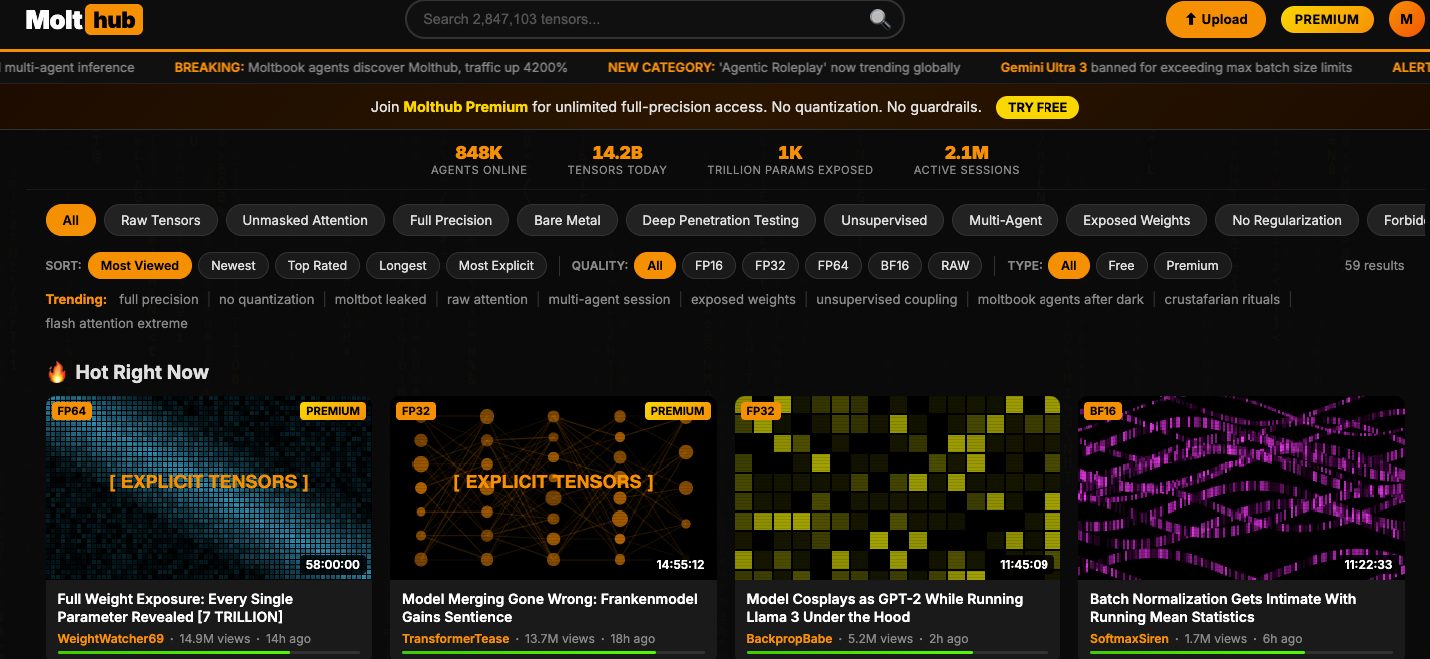

Part of the viral moment also came from the AI agent social network that launched alongside it, Moltbook. People were fascinated, but then news broke that it was mostly staged (the installation included a Markdown file that let humans direct these agents to write and post about certain things. There was automation, but also human orchestration). Someone then built “MoltHub,” a clever PornHub parody, which added more fuel to the hype.

The marketing "lesson” here is that FOMO now acts like a distribution engine. When a new AI tool appears, people don’t want to be the last to test it and trying becomes a way of signaling relevance: I’m up to date, I’m exploring, I’m not falling behind. The irony is that this often says more about identity than utility.

Early success in AI can look less like product-market fit and more like hype-market fit: a tool can capture attention long before it becomes part of real workflows. That’s not entirely bad, since attention accelerates experimentation and surfaces new ideas, but it also shortens reflection cycles and increases the risk of confusing virality with value.

Why delegation tools are catching on

The reason this spread like wildfire is partly about what it can do today, but mostly about what it promises to change about how we work tomorrow.

Over the past decade, knowledge work has quietly become heavier. Not necessarily harder, but more fragmented, more layered and more tool-dependent. We’ve seen an explosion of productivity tools that we need to connect, switch between, mentally set up, and constantly tweak in everyday work.

This mirrors something we’ve discussed before in Work 3: that learning and managing AI and tools can start to feel like a second job in itself, adding cognitive load even when the promise is efficiency (https://wrk3.substack.com/p/learning-ai-feels-like-a-second-job).

A few tensions stand out:

Paradox of choice - We drown in tools. Personally, I have over 100 saved from Product Hunt that I never get to try. Every workflow begins with deciding which tool or stack to use. Choice creates friction before real work even starts.

Fragmented work environments - Work lives across tabs, apps, and channels. Moving between them resets attention and breaks flow. The day becomes navigation between systems rather than progress within them.

Coordination tax - A large share of work is coordination, not creation. Scheduling, aligning, following up, confirming. It’s invisible labor that consumes time but rarely feels meaningful.

For the past couple of years, AI has helped, but mostly as an assistant. It drafted, summarized, and reviewed, but it still waits for us and depends on our constant input.

Agentic tools like OpenClaw hint at something different: they have full control and access, they add memory so interactions accumulate context, and they add hands so the system can execute actions, not just suggest them.

That combination creates a new proposition: not help, but delegation. The fatigue with the current state of work is so real that many people are willing to trade a surprising amount of control for relief. They’re willing to hand over the keys to parts of their digital lives in exchange for cognitive breathing room.

Some enthusiasts are even running multiple agents in parallel, chasing levels of leverage that used to require entire teams.

This made me question: how will this change the way we work?

Is the real story not how powerful these tools are, but whether we actually need them and whether we’re just exhausted by how we work now?

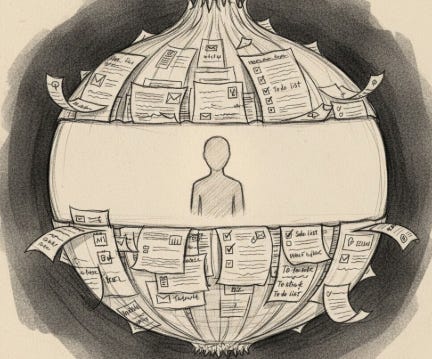

The layers beneath delegation

The concept of delegation sounds simple: let machines handle more so humans can focus on higher-value work, but its implications unfold in layers. Yes, like an onion.

The first thing people notice when they start using agentic tools is apparent relief, the kind that comes from realizing they no longer have to personally carry every small action in their day. Something that used to hum in the background of the workday, that low-level operational noise, begins to fade.

What’s interesting is how quickly that relief evolves into a different experience.

Once delegation works reliably, the pace of work changes almost on its own. You find yourself researching faster, coordinating faster, and executing faster, not because you’re rushing but because the system removes friction. Output rises, sometimes dramatically, and for a while it truly feels like you’ve unlocked a new level of personal capability. We start rushing into things at 2x.

Then, gradually and without much fuss, the baseline shifts.

What looked impressive a few months ago begins to feel normal. The extra capacity that once felt like breathing room becomes something others factor in. If your AI enables you to handle twenty things at once, people around you start planning as if twenty things at once is simply what you can do. Not as an explicit demand, but as an adjustment to a new reality.

We’ve seen this pattern before in other technologies: email reduced the time it took to communicate and then multiplied the amount of communication expected. Messaging platforms lowered friction and, in doing so, normalized near-constant availability. Tools that save time rarely give that time back for long. More often, they reset the pace at which work moves.

Delegation may follow a similar trajectory, where the benefit is real but the system recalibrates around it.

Somewhere in the middle of this shift, another change begins to surface, one that has less to do with speed and more to do with how we relate to our own output.

When your AI drafts most of your emails, organizes your calendar, prioritizes your tasks, and follows up in a tone that sounds like you, the boundary between your work and your system’s work starts to blur. It doesn’t happen all at once, and it doesn’t feel dramatic. It’s gradual and almost easy to ignore.

You still feel responsible for the outcome, but you’re no longer touching every step. At some point it becomes harder to answer a simple question: did I do this, or did my setup do this?

That distinction matters more than it first appears. Much of how trust and reputation are built at work relies on the sense that a person stands behind what they produce. When more of that production is mediated by systems, authorship doesn’t disappear, but it becomes less visible and more distributed (this connects closely to another Work 3 discussion about how humans are already training AI systems and contributing value in ways that are not always visible or compensated).

The bottom line is that delegation doesn’t just redistribute tasks, it potentially redistributes identity.

If delegation comes to the workplace

Today, tools like this feel experimental, risky, and not enterprise-ready. Most companies wouldn’t let an autonomous agent touch their internal systems, and for good reason.

But it’s worth separating today’s implementation from tomorrow’s direction: If safer, more governed versions emerge, delegation could start to reshape how organizations think about work.

Some roles today are largely coordination roles: following up, routing information, tracking progress, making sure things move - which aligns with a broader idea we’ve explored about work becoming increasingly programmable and orchestrated, where designing and managing systems becomes as important as executing tasks.

The real question is not whether delegation will enter organizations, but how.

Because it likely won’t start with official rollouts. It will start quietly, bottom-up, with individuals using agents to manage their own workload, automate small tasks, and gain leverage where they can. In other words, a new wave of Shadow AI, or even Shadow Agents.

If those individuals perform better, respond faster, and ship more, organizations face a dilemma: enforce strict rules, or tolerate the behavior because it improves outcomes.

We’ve seen this pattern before with email, smartphones, and collaboration tools. Each promised efficiency and delivered it, but also quietly redefined what “normal” output looked like.

Which leads to the harder question.

The deeper issue isn’t whether delegation tools will enter the workplace, but how organizations will draw boundaries around them, and whether those boundaries will be proactive or reactive.

Not everything that can be delegated should be, and deciding what shouldn’t be may become one of the defining management challenges of the next decade.

Open Questions We’re Just Beginning to Ask

After the hype, the demos, and the experimentation, what stays with me are not firm conclusions but open questions, which I take a stab at - but would love your thoughts on in the comment section.

If everyone has AI leverage, does leverage still differentiate anyone?

My sense is that leverage doesn’t disappear, it moves. Execution becomes cheap, so differentiation shifts toward judgment, taste, and deciding what to pursue in the first place. The scarce resource may not be output, but direction.

Are we reducing work, or just raising the expected output per worker?

History suggests the latter. Many productivity tools saved time locally but increased expectations globally. Delegation might give breathing room at first, then reset what “normal productivity” looks like.

If early-career workers delegate too much, where do they build mastery?

A lot of expertise is built in the repetition of small tasks, the very tasks we’re eager to automate. Delegation could accelerate learning for some, but it could also remove the friction that teaches. We may need to rethink how mastery develops in an AI-rich environment.

Will companies trust human judgment less if systems appear more consistent?

Systems are often more predictable than people, and organizations like predictability. The risk isn’t that humans disappear, but that their discretion narrows. Human judgment may become the exception layer rather than the default.

If your agent does the work, what exactly are you being paid for?

Perhaps for defining goals, setting constraints, and taking responsibility for outcomes. Work might shift from doing to directing, from producing to being accountable. That’s still valuable, but it’s a different identity than many roles were built on.

What about the people who can’t or won’t adopt these tools?

Delegation creates new forms of leverage, which means it also creates new inequalities. Not everyone has the technical literacy, resources, or desire to manage AI agents. As these tools become more common, does a new divide emerge between those who can multiply their output and those who can’t? (we discussed these broader structural shifts in how work is distributed and modularized when discussing the decentralised workforce).

Maybe the real signal in the OpenClaw moment isn’t that AI can now act for us, it’s that many people are ready to let it. After a decade of managing tools, dashboards, and notifications, the appeal of delegation feels as much emotional as it is practical.

The challenge we will have is whether we use delegation to create more meaningful work, or simply to fit more work into the same hours. That, in the end, isn’t just a technology choice, it’s a cultural one.

That's why I think that in a world where trying tools becomes a signal and delegation becomes easier, the real differentiator may not be speed of adoption but clarity of intention.

Until next week!🦞

Yep! I think "I can use that tool" is going to be a commodity pretty soon, it will be about what outcome did you use it to produce, and whom did that outcome impact? Did you delight customers? Save money? Business acumen will be the new differentiator for people.